Astro Info Service Limited

Information Research Publications Presentations

on the Human Exploration of Space

Established 1982

Incorporation 2003

Company No.4865911

E & OE

Apollo 8 Part 4

APOLLO 8 MISSION REPORT

Part Four - Coming Home

The concluding part of our in-depth mission report on Apollo 8 covers the trans-Earth period of the mission, bringing the spacecraft and crew back from the Moon to recovery in the Pacific Ocean. A selection of titles and references for further reading into this fascinating and pioneering mission is provided at the end of this report.

Trans-Earth Coast

The trip back home from lunar orbit would take over 57 hours, from the Trans-Earth Insertion (TEI burn) to the point of entry into Earth's atmosphere. During the two-day journey home, the astronauts completed star and navigation sightings using the horizons of Earth or the Moon. As with the flight out to the Moon, thermal heating and cooling of the spacecraft's surface and inner components was maintained evenly with a roll rate of 360 degrees each 60 minutes. The alignment of the trajectory back to Earth was so precise that only one small 15-second mid-course correction burn was required at 120 hours into the mission on 25 December, changing the velocity by just 1.5 m/sec (4.8 fps).

It was Christmas Day and the crew had discovered Christmas presents from their wives that had been specially stowed aboard the spacecraft. Christmas greetings to and from the spacecraft were featured in messages throughout the day. They also completed another telecast from the Command Module (CM), their fifth of the mission, which lasted 9 minutes and 31 seconds. With most of the mission's objectives completed and by now well on their way back, the crew gave a guided tour of their 'home'. Jim Lovell demonstrated the operation of the 'Exer-Genie', a device used for in-flight exercise on their mostly unused legs, while Bill Anders demonstrated preparing and eating some of the dehydrated food in space. Frank Borman commented that he hoped Earth-bound viewers were having a better Christmas lunch than they were before going on to explain the navigational system and onboard computer to the TV audience.

Following this TV show, the crew found a special treat inside the food locker. Each man had food packages clearly marked for breakfast, lunch and dinner and these were foil-wrapped according to the flight day. When they unpacked their evening meal on 25 December, however, they found it had been specially prepared with 'Merry Christmas' messages and wrapped in foil with decorative (and fireproof) red and green ribbons. Instead of the rather bland dehydrated meals they had consumed for the last five days, they found real turkey meat in gravy with stuffing and cranberry sauce. In his autobiography, Borman later wrote that this was by far the best meal of the whole trip, though he banned the consumption of three miniature bottles of brandy that had been sanctioned by their boss Deke 'Santa' Slayton. Not that Anders or Lovell had intended to open them anyway, in case any future error might be attributed to the consumption of the liquor.

Losing the Platform

Ironically, something did go wrong not long after eating their dinner. Jim Lovell had proceeded to take more navigational sightings from the navigation station, but he accidentally hit the erase button that dumped the navigational data from the computer. With the platform lost, the thrusters began to compensate for the apparent loss of orientation. The computer was able to stabilise itself, but only in what it assumed to be the vertical launch position on the Saturn V back on the launch pad. This, of course, was useless for the re-entry, as there was no accurate way to tell the computer which way was 'up'. Lovell had to realign the platform manually by taking sightings of known stars and aligning the spacecraft to them. It took him over 15 minutes ro reprogram the computer with enough information for it to be able to distinguish the spacecraft's orientation in the void of space. With the task completed, Lovell received enquiring looks from Borman and Anders and, with an embarrassed grin, told them not to worry and that all was fine.

The following day, the crew gave their sixth and final telecast, of 19 minutes 54 seconds, which focused mainly on the approaching Earth that was steadily growing larger in their window. Anders was amazed that they had travelled all that way to the Moon and back, only to be fascinated by the sight of this blue ball floating in space, now pulling them home. He commented to Mission Control that it seemed to him that mariners on old sailing ships must have had the same feelings as they approached land. To Lovell, the Earth still looked small, as he could block out the whole globe - and all of human history - with his thumb held at arm's length.

Most of the last full day in space was taken up with waiting and reflecting. There was nothing much the crew could do except monitor the spacecraft, talk to Mission Control and wait for re-entry the next day.

Return to Earth

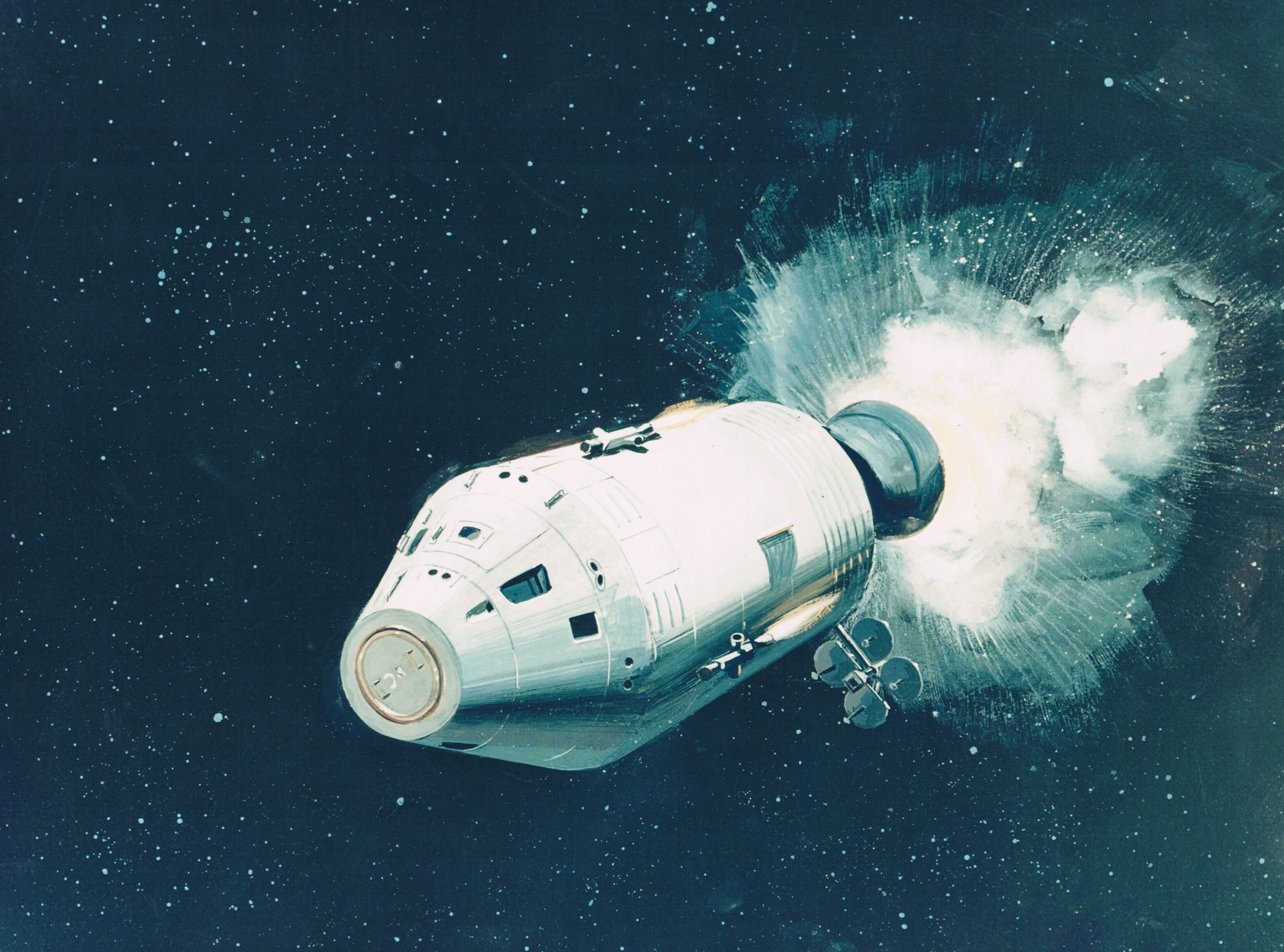

As 27 December dawned across the Pacific Ocean, the crew were preparing to separate their faithful Service Module (SM) and orientate the CM around to face the blunt end - and its heat shield - towards the atmosphere. Separation occurred at Ground Elapsed Time (GET) 146 hours 28 minutes 48 seconds, with the CM following an automatic guided entry profile. Shortly after separation, the crew noticed the Moon rise over the limb of Earth as they streaked towards home.

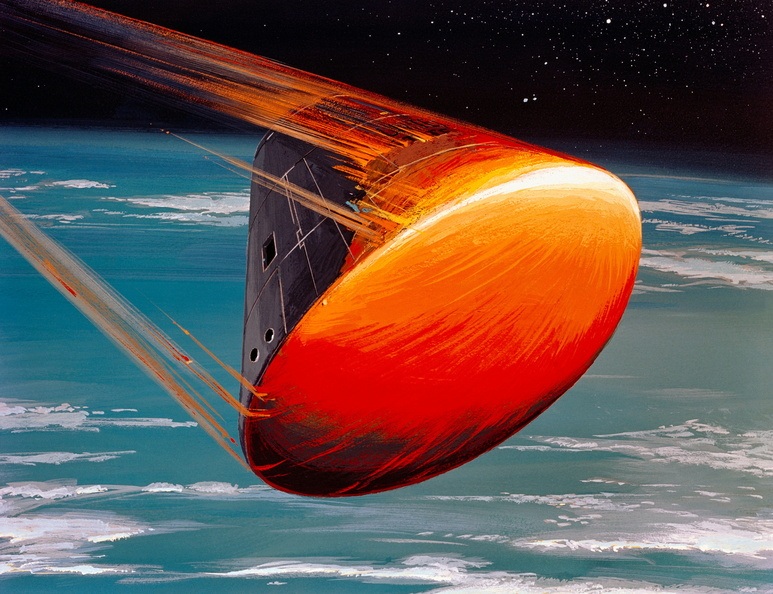

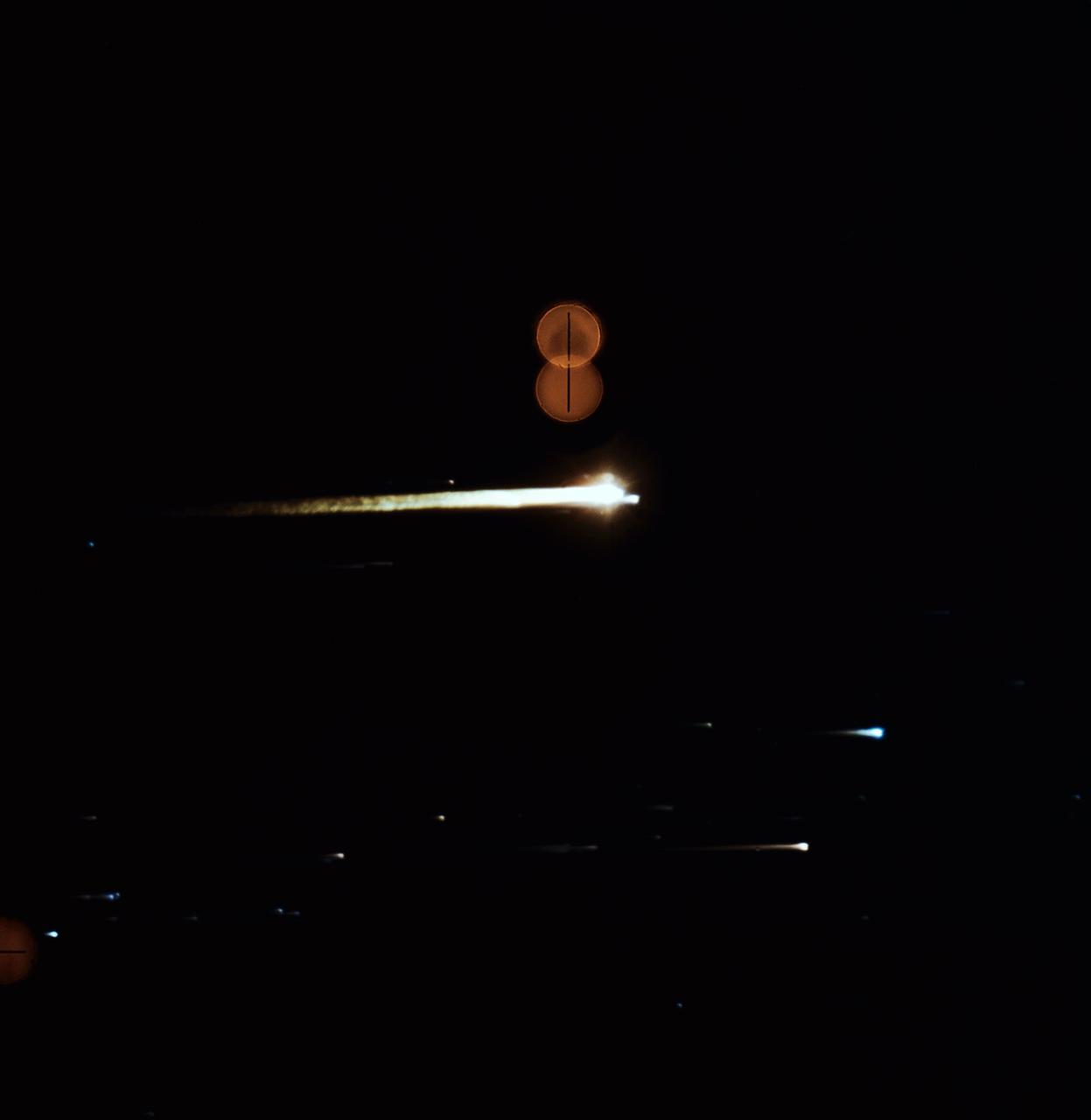

Entry into the atmosphere occurred at 121,920 m (400,000 ft) and at GET 146 hours 46 minutes, travelling at 11,040 m/sec (36,221 fps). After a trans-Earth trajectory flight of 57 hours 23 minutes and 32.5 seconds, the recovery phase had begun, with the crew fully aware of it. As the spacecraft skipped through the atmosphere, the g-loads increased to six times that of Earth's gravity. Coming after six days of weightlessness, the crew felt as though they had elephants sitting on their chests. Inside the CM, the cabin was bathed in the bright blue light of the ionisation from the flaming entry sheath.

The parachute system operated as designed, gently slowing the spacecraft towards its splashdown in the Pacific in the early dawn of 27 December, after a flight of 147 hours and 42 seconds. The spacecraft landed at estimated coordinates of 8.10°N and 165.00°W, some 2.6 km (1.4 nautical miles, nm) from its pre-launch landing target and 4.8 km (2.6 nm) from the prime recovery ship, the USS Yorktown. The impact with the ocean had upturned the CM, so the crew found themselves hanging in their straps looking at the depths of the ocean through the spacecraft windows for six minutes, before three self-righting balloons inflated to turn the spacecraft over into the upright position.

A Moon of American Cheese

Sunrise occurred 43 minutes after splashdown, as pararescue divers dropped into the ocean from helicopters to secure the spacecraft. Inside, the three astronauts awaited the pick-up, with Borman suffering the worst from the heavy ocean swell. As the rescue helicopters circled, the pilots asked the crew if the Moon was made from Limburger cheese, to which they replied: "No... it's made of American Cheese."

With the floatation collar attached, the crew disembarked from the spacecraft, taking their first gulps of fresh air in almost a week. One by one they were hoisted aboard one of the helicopters, to be taken to the Yorktown. They stepped on the deck of the recovery ship 88 minutes after splashdown and were followed there an hour later by the now-empty CM which had logged 933,419 km (504,006 nm).

A Mission to the Moon

The mission of Apollo 8 was over, but the post-flight debriefing and evaluation was just beginning. The crew and hardware had proved that the Apollo-Saturn V system could support a crewed Command and Service Module (CSM) flight to the Moon, operate in lunar orbit and complete the return leg without serious difficulty. Following the series of uncrewed missions and then the flight of Apollo 7 two months before, the CSM was now qualified for lunar operations. The hardware for the next two missions - Apollo 9 and Apollo 10 - was already at the Cape. Those two missions would be used to put the final element of the lunar programme through its paces - the Lunar Module (LM). If all went well on those two flights, Apollo 11 would be targeted for the first lunar landing attempt in the summer of 1969. Indeed, the crew for that mission was announced on 9 January 1969, barely two weeks after Apollo 8 returned home. After months of delay and frustration following the tragic Apollo 1 pad fire in January 1967, the Apollo programme was at last gearing up to reach President Kennedy's lunar goal within the next 12 months.

Afterwards

Of the Apollo 8 crew, only Jim Lovell flew in space again, this time as Commander of Apollo 13 in April 1970. He had hoped to complete the final 69 miles of his journey to land and walk upon the lunar surface, but history tells us it was not to be, although the events of that mission and the dramatic recovery of the crew have become more famous to a wider audience, due to Lovell's book and subsequent feature film, than Apollo 8 has. Lovell would be the only Apollo astronaut to go to the Moon twice without landing on its surface. Frank Borman left NASA in 1970, with Bill Anders having already departed in 1969. Lovell finally left in 1973 and all three moved on to new achievements and careers.

With the mission having flown almost 60 years ago, it is perhaps not surprising that all three astronauts have passed away, although only in recent years and with each having reached their 90s. Borman died on 7 November 2023 at the age of 95, Anders on 7 June 2024 aged 90 and Lovell most recently on 7 August 2025 aged 97. They will forever be known as the first men to fly to the Moon.

Apollo 8 paved the way for the Apollo missions that followed it, but it was much more than the vanguard for Apollo to explore the Moon. It was also the pioneering voyage out from Earth orbit that will be remembered not only by the next generation of lunar explorers but also by those who embark on the even longer first flight out to Mars and perhaps beyond.

As with Yuri Gagarin being remembered as the first man to fly into space and Alexei Leonov as the first to walk in space, Apollo 8 will forever be the mission that was the first to "slip the surly bonds of Earth" and venture 'out there'. Let us hope it will not be much longer before we see the resumption of voyages to the Moon.

References and Suggested Reading

In the compilation of this extended mission report, the following publications were valuable sources of information and data and are suggested for further reading into the pioneering mission.

Apollo 8: Man Around the Moon, NASA EP-66 1969. The 24-page NASA Public Affairs booklet issued shortly after the mission, which is full of photos of the preparations and flight. Now a much sought-after collectors' item.

Apollo 8: A Most Fantastic Voyage, Sam Phillips, National Geographic magazine, May 1969. An early interpretation and account of the first mission to the Moon, with stunning photos. Also now a collectors' item.

Countdown, Frank Borman with Robert J. Sterling, Silver Arrow Books, New York 1988 (ISBN 688-07929-6). The biography of Apollo 8's commander.

A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts, Andrew Chaikin & Michael Joseph, London 1994 (ISBN 0-7181-3842-2). The excellent chronicle of the Apollo missions using original interviews with many of the Apollo astronauts. It features a chapter on Apollo 8 which focuses the story from Bill Anders' point of view.

Lost Moon. The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13, Jim Lovell & Jeffrey Kluger, Houghton Mifflin, New York 1994 (ISBN 0-395-67029-2). Though mainly focusing on Lovell's next mission, Apollo 13 and his return to the Moon, there is a section describing his activities on Apollo 8.

Genesis: The Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman. Four Walls Eight Windows, New York 1998 (ISBN 1-56858-118-1). Written to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the flight and with the full cooperation of the astronauts and their families, this is an excellent account of "the first manned flight to another world", as the sub-heading states. Zimmerman blends the details of the mission and accounts of the three astronauts into an entertaining story.

Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference, Richard Orloff, NASA SP 2000-4029, 2000. A resource of official NASA facts and figures for all the crewed Apollo missions in order of flight, including a section on Apollo 8.

Apollo 8: The NASA Mission Reports, 2nd Edition, Edited by Robert Godwin, Apogee Books, Ontario 2000 (ISBN 1896522-66-1). A collection of six of the most important mission documents from the NASA archives: The Press Kit; Pre-Mission Report and Objectives; the Supplemental Technical Report; the Post-Flight Summary; the Post-Flight Mission Operations Report; and the Post-Flight Crew Debriefing. The bonus CD ROM also includes an interview with Jim Lovell, the crew debriefing and post-flight mission report. A handy collection of historical documents with a colour photo insert.

Apollo 8 Flight Journal: http/nasa.gov/history/afj/ap08fj/index.htm. This is an excellent online source of information, compiled by David Woods and Frank O'Brien, that follows the flight of Apollo 8 using the air-to-ground commentary, onboard tapes and post-mission debriefings. It also includes additional information sources and references and is linked to other sites covering flight operations of the Apollo 11 mission and the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal that covers the surface operations of the six Apollo lunar landings.

This Mission Report is copyright Astro Info Service Ltd 2003, 2025

All images are courtesy of NASA, unless otherwise stated.

Artist's impression of the critical firing of the SPS engine to enable Apollo 8 to break free from lunar orbit and head home.

TV viewers saw this picture of Earth during the sixth live telecast from Apollo 8 as the spacecraft headed home. At this point, the spacecraft and its crew were about 179,644 km (97,000 nm) from Earth and travelling at approximately 1,854.5 m/sec (6,084 fps).

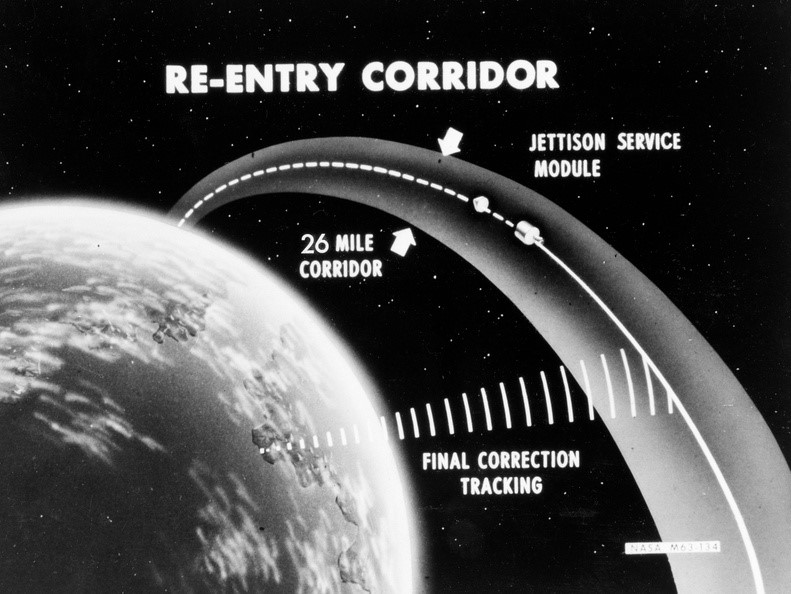

This diagram shows the planned final moments of Apollo 8's return to Earth and re-entry into the atmosphere.

This North American Rockwell Corporation artist's impression of re-entry shows the spacecraft flying blunt end forward to present the heat shield towards the atmosphere. The red colouration illustrates the intense heat the spacecraft would face as it descended.

Image courtesy of North American Rockwell Corporation and NASA.

Taken by the USAF Airborne Lightweight Optical Tracking System (ALOTS) camera mounted on a KC-135 aircraft flying at 12,192 m (40,000 ft), this image shows the fiery re-entry of Apollo 8 as it heads through the atmosphere.

Image courtesy of the US Air Force and NASA

US Navy frogmen participate in the recovery operations after Apollo 8 splashes down, with the crew picked up by helicopter and taken to the USS Yorktown recovery ship. The spacecraft followed them about an hour later.

The Apollo 8 crew (l to r) Borman, Lovell, Anders stand in the doorway of a recovery helicopter after arriving aboard the carrier USS Yorktown less than 90 minutes after splashdown.

Three days after returning to Earth, the Apollo 8 crew (l to r) Lovell, Borman and Anders, participate in a technical debriefing session in Building 4 at MSC Houston.