Astro Info Service Limited

Information Research Publications Presentations

on the Human Exploration of Space

Established 1982

Incorporation 2003

Company No.4865911

E & OE

Apollo 8 Part 3

APOLLO 8 MISSION REPORT

Part Three - Christmas Around the Moon

Having examined the journey of Apollo 8 from Earth to the Moon in part two of this in-depth mission report, for this third instalment we cover the period that the three astronauts spent in lunar orbit over the Christmas holiday of 1968. Ten orbits were completed in 20 hours as humans travelled to another world for the first time.

"We Got It, We Got It"

Slipping behind the Moon for the first time, the three astronauts were amazed at how precisely communications from Earth ceased, exactly to the flight plan. Light-heartedly, they commented to themselves that the Flight Director (FD) Chris Kraft had probably told the flight controllers to turn off the radio anyway, no matter what happened.

It was a busy time inside the spacecraft, as they had to prepare for the four-minute burn of the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine on the Service Module (SM) to slow their trajectory sufficiently to be captured in lunar orbit. When they looked out of the windows, all they could see was the black void of space with no Moon in view. But then Bill Anders noted, as he looked out, that a dark, starless void was creeping towards them and they realised that the Moon, in shadow, was very close. The crew waited in silence for the countdown to ignite the engine and begin the Lunar Orbit Insertion (LOI) burn. As they approached lunar sunrise, they turned off the lights in the cabin. Jim Lovell was the first to see their target outside, exclaiming, "Hey! I got the Moon!" It was directly beneath them and as Anders also caught sight of the cratered surface, he could not help but comment, "Oh my God!" This drew Frank Borman's attention. As his colleagues were trying to identify the "holes and bumps", he pointed out that they needed to get their concentration back to the task in hand. With less than a minute to the LOI burn there was a lot to do, but if it worked successfully they would have plenty of time to look at the view later.

The ignition for the burn began at 69 hours 8 minutes and 20.4 seconds into the mission and lasted for 246.9 seconds (4 minutes 6.9 seconds), resulting in an initial elliptical orbit of 312 x 111 km (168.5 x 60 nautical miles, nm), travelling at 1.663.6 m/sec (5,458 fps). Strapped into their couches after three days of zero-g, even this small force of gravity felt like 3G to the crew. As the seconds ticked by, the three men knew that everything needed to work correctly to ensure that they did not crash onto the Moon or end up in a wrong orbit that they might not easily get out of. But with the SPS firing, at least they knew they were not going to come home for a while. Each of the astronauts felt that this was the longest four minutes of their lives. Even though the computer automatically terminated the burn, Borman still pressed the manual cut-off switch, "...just in case". After a quick visual check, the crew congratulated themselves on a successful burn. There were still the small matters of firing the engine once more so that they could come home and then the first crewed re-entry from deep space, but for now they prepared their cameras to take as many photos as possible, in case they had to return home early.

At the time of the shutdown, it would still be another 25 minutes before the spacecraft could re-establish contact with Earth, so for the controllers and the families of the astronauts, it was an anxious wait. The Capcom on duty was Jerry Carr and, as the time for the Acquisition of Signal (AOS) approached, he began calling up to the spacecraft every 15 seconds: "Apollo 8, Houston, over... Apollo 8, Houston, over..." Each call was greeted with static, as Carr hoped not to receive a reply too early which would indicate a major problem. Then suddenly, there was an excited outburst from Mission Control: "We got it. We got it..." Then came loud applause and cheers from the support and viewing rooms as Lovell cooly responded to one of Carr's calls: "Go ahead Houston. This is Apollo 8. Burn complete." Carr responded: "Apollo 8, This is Houston. Roger, good to hear your voice." The crew reported the facts and figures from their successful burn, but everyone realised it all meant that Apollo 8 was safely in lunar orbit. No one would get much rest over the next day or so, but success was beginning to sink in as the crew began the first of ten orbits around the Moon, an early Christmas present to the programme.

"The Moon is Essentially Grey..."

Capcom Jerry Carr, hoping to go to the Moon himself on one of the later Apollo lunar landing missions, was naturally curious about the view out of the spacecraft windows. He asked: "What does the ol' Moon look like from 60 miles?" Lovell gave the crew's first impressions: "Ok Houston, the Moon is essentially grey. No colour. Look like plaster of Paris... or sort of greyish beach sand. We can see quite a bit of detail."

Borman requested that he should receive a verbal "Go" for every revolution, so that if there was no such authority to proceed, he would assume that they had to get home at the next opportunity. The responsibility of command was natural to him and he would let his colleagues take the lead with the descriptive reports and photography.

For the next 12 hours, the crew conducted their primary photography task, especially focusing on the landing areas planned for the next few missions and in particular, Site Number 2 on the Sea of Tranquility. They snapped away at targets on the near and far sides, obtaining vertical and oblique overlapping (stereo) images that would help determine the elevation and locations on the far side. They used the cameras through the sextant for potential landing sites, to obtain navigational and training views for later crews who might visit the location. Where necessary, they also photographed targets of opportunity and obtained coverage of specific features or areas that had not been photographed by the Lunar Orbiter robotic space probes.

Flight analysis of the Apollo 8 photography allowed NASA to evaluate the illumination levels from the surface. The crew added to the photographic record with their verbal descriptions of the surface as it passed below them. In total, from over 800 shots taken, there were some 600 good quality 70 mm still photo frames of lunar surface features. Most of the 213 m (700 ft) of exposed 16 mm film was used for lunar landmark photography via sextant and surface sequence photography. The cameras were also used to record IVA activity, S-IVB separation and venting and long-distance views of Earth and the Moon. The crew provided valuable information for mission planners both for orbital missions and landing flights. One of the major discoveries of the mission came from analysis of each orbit, which revealed that mass concentrations (later named 'mascons') were shifting the orbital parameters slightly. At Ground Elapsed Time (GET) 73 hours 35 minutes into the mission, their third orbit was circularised at 112.4 x 110.5 km (60.7 x 59.7 nm) by a 9.6-second burn of the SPS. The final orbit was measured at 117.8 x 108.5 km (63.6 x 58.6 nm) without any further engine burns.

The crew continued to describe the Moon during each near-side pass and though their interpretations of the colours of the surface changed with the lighting conditions, they confirmed they could identify landmarks in the shadow zones and in extremely bright areas, even though these were not well defined in the subsequent photography. Using this combination of crew interpretation and orbital photography, the lunar surface lighting conditions constraints for the forthcoming landing missions were amended.

As they orbited the Moon, the crew added names to several new landmarks, mountains, craters and other features. Their first TV cast from around the Moon was broadcast during their second orbit and for 11 minutes, Anders described what the Earth-bound viewers were seeing on their screens, adding his impressions of the colour of the Moon as, "... like a very whitish grey, like dirty beach sand with lots of footprints in it. Some of these craters look like pickaxe striking concrete, creating a lot of fine dust haze. You can see by the numerous craters that this [the Moon] has been bombarded through the eons with numerous small asteroids and meteoroids pockmarking the surface every square inch." Anders added, "The back side [of the Moon] looks like a sand pile my kids have played in for some time. It's all beat up, no definition, just a lot of bumps and holes." An example of the details revealed by the crew was this description of one feature by Lovell: "Langrenus is quite a huge crater; it's got a central cone to it. The walls of the crater are terraced, about six or seven terraces on the way down." Anders also commented on the blackness of space: "The sky is very, very stark. The sky is pitch black and the Moon is quite light. The contrast between the sky and the Moon is a vivid dark line."

Earthrise

During the first few orbits, the three astronauts were so busy they did not notice the view that greeted them as they emerged from the far side of the Moon. On their fourth orbit, Borman needed to roll the spacecraft to allow Lovell to take a navigational sighting. As Borman looked out of the window, his attention was taken by the only splash of colour in an otherwise stark black-and-white view. The Earth was rising over the limb of the Moon. They realised they had to photograph the sight, relishing its beauty and distance. No one had thought to place an Earthrise shot in the mission objectives, but each of the three astronauts realised how impressive the scene was. Racing to capture the photos, they took hurried shots in both black-and-white and colour. Lovell questioned whether Anders had captured the view and his colleague assured him that he had indeed snapped a couple of frames, but he was sure that the view would come up again in a few hours. These 'couple of frames' became some of the most famous photos taken from a human space flight and remain iconic symbols of the achievements of the Apollo programme almost 60 years after they were taken.

During the next two orbits, Borman dozed. It had been a very long day and the men needed some rest before starting on the long flight home, so they took turns catching up on some sleep. Anders noted that he was a little disappointed in the view of the battered lunar surface, half expecting the stunning jagged peaks of science fiction stories instead of the rounded mountain ranges he could see below them, although he knew that was what he would find. With Borman awake once more, all three contemplated their situation at this point. Lovell looked out of the window and asked his colleagues if they had ever thought in past years that they would be orbiting the Moon at Christmas one year. Anders quipped that they had better hope they were not still doing it a week later in the New Year, which earned him a "think positive" comment from Lovell.

As his colleagues took their turns to rest, Borman looked after the spacecraft. Asking the Capcom how the weather was back on the distant planet he could see out of his window, he received an update of local and global weather patterns, including those from the primary recovery area of the Pacific Ocean. Capcom Ken Mattingly also noted that news from the recovery areas included the comment that "there's a beautiful Moon out there..." As he looked out of the spacecraft window, Borman wistfully replied: "Yes, I was just [thinking] there's a beautiful Earth out there."

By their eighth revolution of the Moon, all three were awake and preparing for the second telecast.

Live from the Moon

With the TV camera pointing out of the spacecraft window at Earth, Borman began the commentary to Mission Control and a worldwide audience: "This is Apollo 8 coming to you live from the Moon. We showed you first a view of Earth as we've been watching for the past sixteen hours. Now we're switching so that we can show you the Moon we've been flying over. Bill Anders, Jim Lovell and myself have spent the night before Christmas up here doing experiments, taking pictures." Inadvertently, the TV camera was accidentally turned off, leaving only their voices across the void of space and adding to the mystery for those on Earth as to where they were originating from.

Borman stated: "The Moon is a different thing to each one of us. I know my impression is that it's a vast, lonely, forbidding-type existence, or expanse of nothing. It looks rather like clouds and clouds of pumice stone and it certainly would not appear to be a very inviting place to live or work." Lovell came on air next, stating: "The vast loneliness up here at the Moon is awe inspiring, and it makes you realise what you have back there on Earth. The Earth from here is a grand oasis in the big vastness of space." Anders then completed the commentary from the trio: "The thing that impressed me the most was the lunar sunrises and sunsets. These in particular bring out the stark nature of the terrain. The camera was then turned back on following a comment from the ground and, after a few more observations, the crew read from the Book of Genesis, starting with Anders.

"In the beginning, God created the heaven and the Earth..." The passage was continued by Lovell and then completed by Borman who, after ending the reading, added: "And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth."

As the transmission closed, it was time to prepare to begin the trip home.

"Be advised, there is a Santa Claus."

Twenty minutes before midnight on 24 December 1968, communications went silent between Mission Control Center (MCC) Houston and Apollo 8 for the tenth time. At the far side of the Moon, the crew were preparing to fire the SPS engine for 2 minutes 18 seconds to start their return home. This engine had to work. There was no back-up. There was no chance of in-flight repair. It would be a tense hour awaiting the news. There was nothing to do but wait... and wait... and wait.

Inside Apollo 8, the three men chatted among themselves about what they had done, what they had experienced... and contemplated what might lay ahead of them if their engine did not fire.

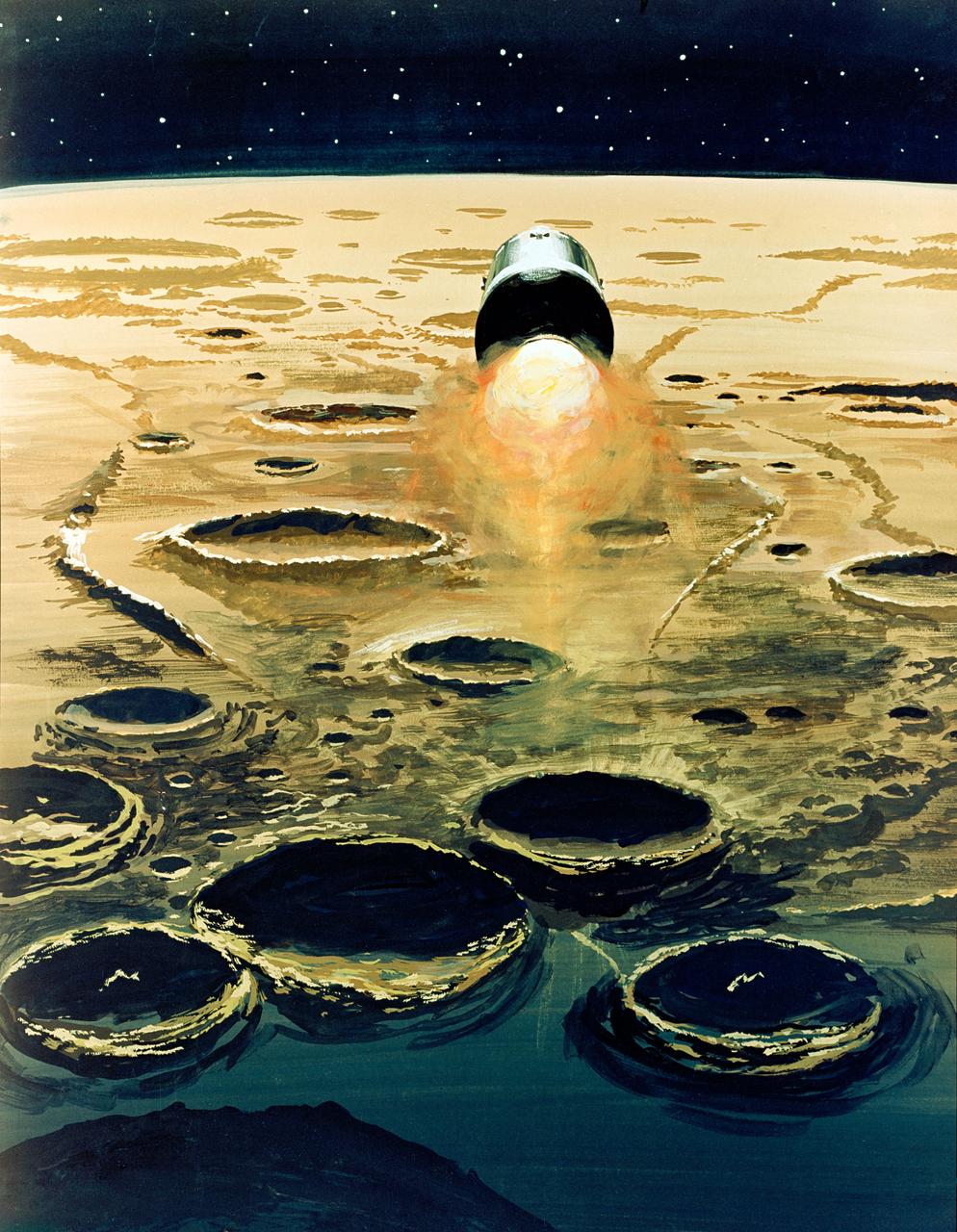

But it did. For 203.7 seconds, the astronauts were once again pinned into their couches. Apollo 8 left orbit after 20 hours 10 minutes and 13 seconds orbiting the Moon. At a velocity of 2,695 m/sec (8,842 fps), they had attained a maximum distance of 377,349.4 km (203,752.37 nm) from Earth and were on their way home. But they were the only ones who knew it.

This time, it was Ken Mattingly's turn as Capcom to call Apollo.

"Apollo 8, Houston." An 18-second break of static. "Apollo 8, Houston." This time 28 seconds of silence. "Apollo 8, Houston." Another 52-second gap. Anything longer would mean there was a serious problem. For the first time in the mission, communications seemed to be playing up, but then, crisp and clear, came the message that all on Earth and in MCC Houston were waiting for, as Jim Lovell proudly exclaimed: "Houston, Apollo 8. Please be advised, there is a Santa Claus." Mission Control erupted in cheers and relief as Mattingly acknowledged that the crew were in the best position to know about that.

Apollo 8 was coming home.

This Mission Report is copyright Astro Info Service Limited 2003, 2025.

All images are courtesy of NASA, unless otherwise stated.

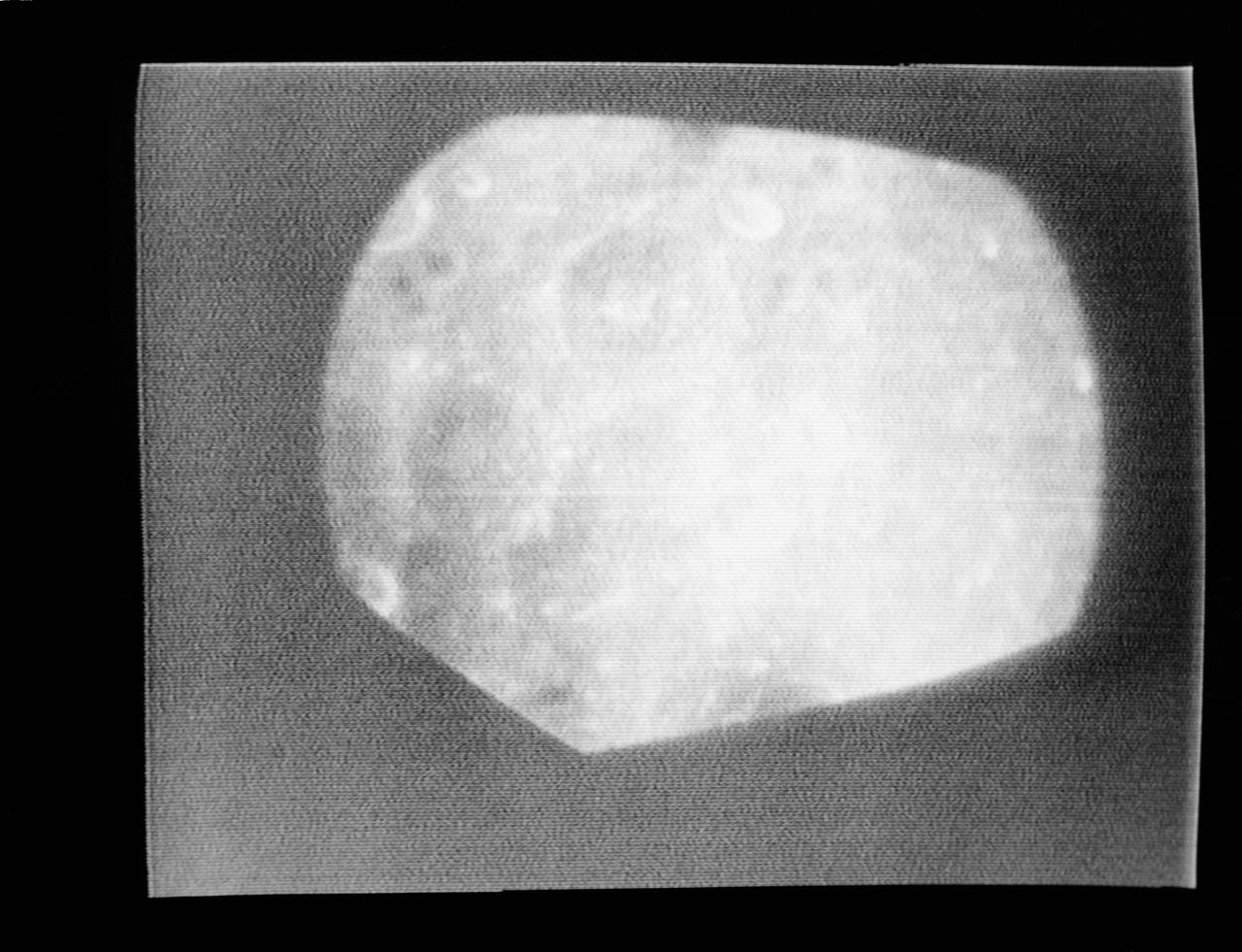

The crew of Apollo 8 were the first to see with their own eyes features such as these on the far side of the Moon.

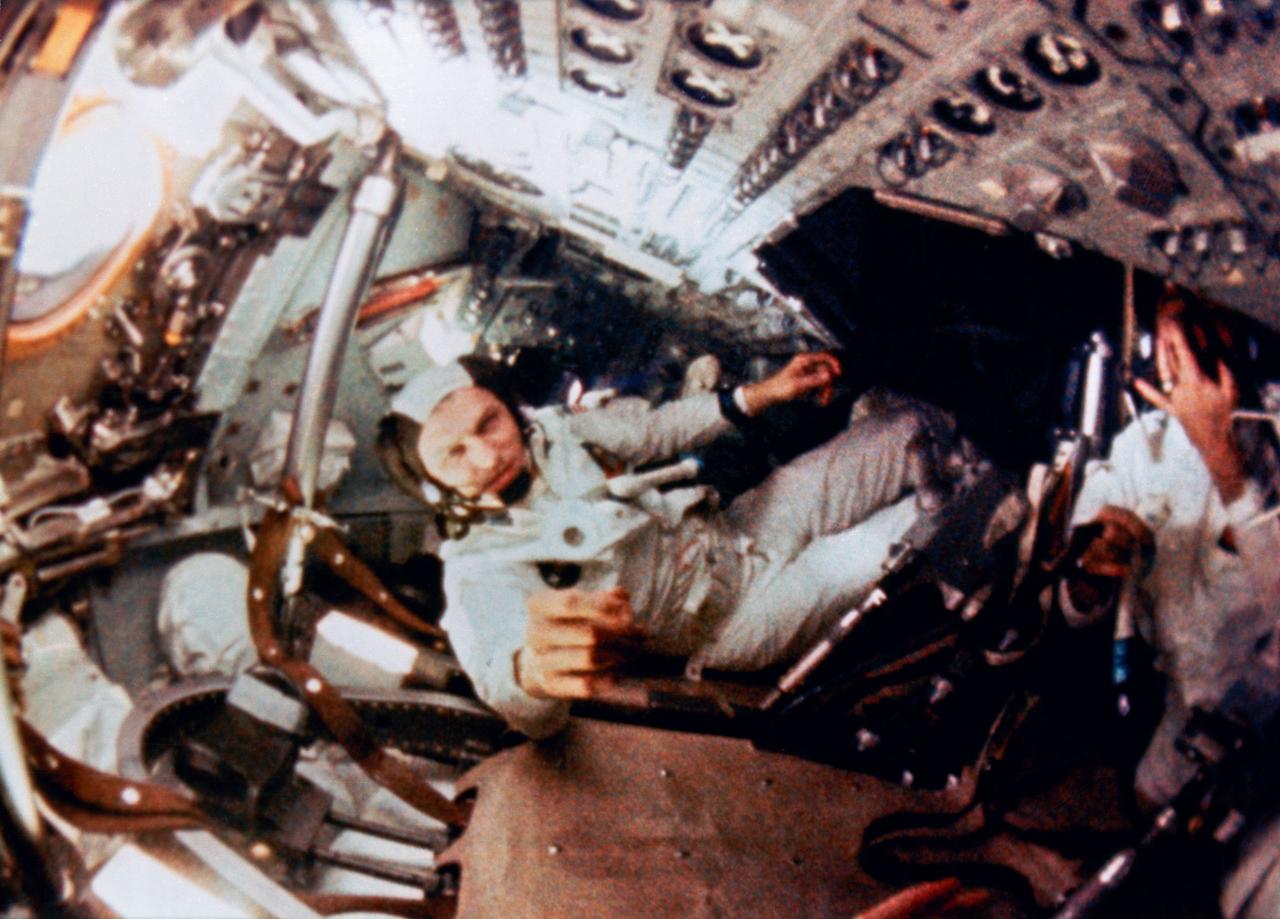

These three intravehicular activity (IVA) still images of Borman (top), Lovell (middle) and Anders (bottom) taken aboard Apollo 8 are prints from 16 mm movie footage shot during the mission.

"The Moon is essentially grey..." In this Target of Opportunity image taken of the lunar far side, the large crater centre left is approximately 110 km (70 miles) in diameter and is located about 200 km (125 miles) south of the spacecraft's position.

This is how the surface of the Moon looked from an altitude of approximately 96.5 km (60 miles) through a TV camera aboard the Apollo 8 spacecraft, during the third live transmission back to Earth on their second lunar orbit.

The iconic 'Earthrise' image taken by the Apollo 8 crew after they finally found time to look out of the window. The image is shown in the orientation that the crew would have seen it as Apollo 8 emerged from behind the Moon once again.

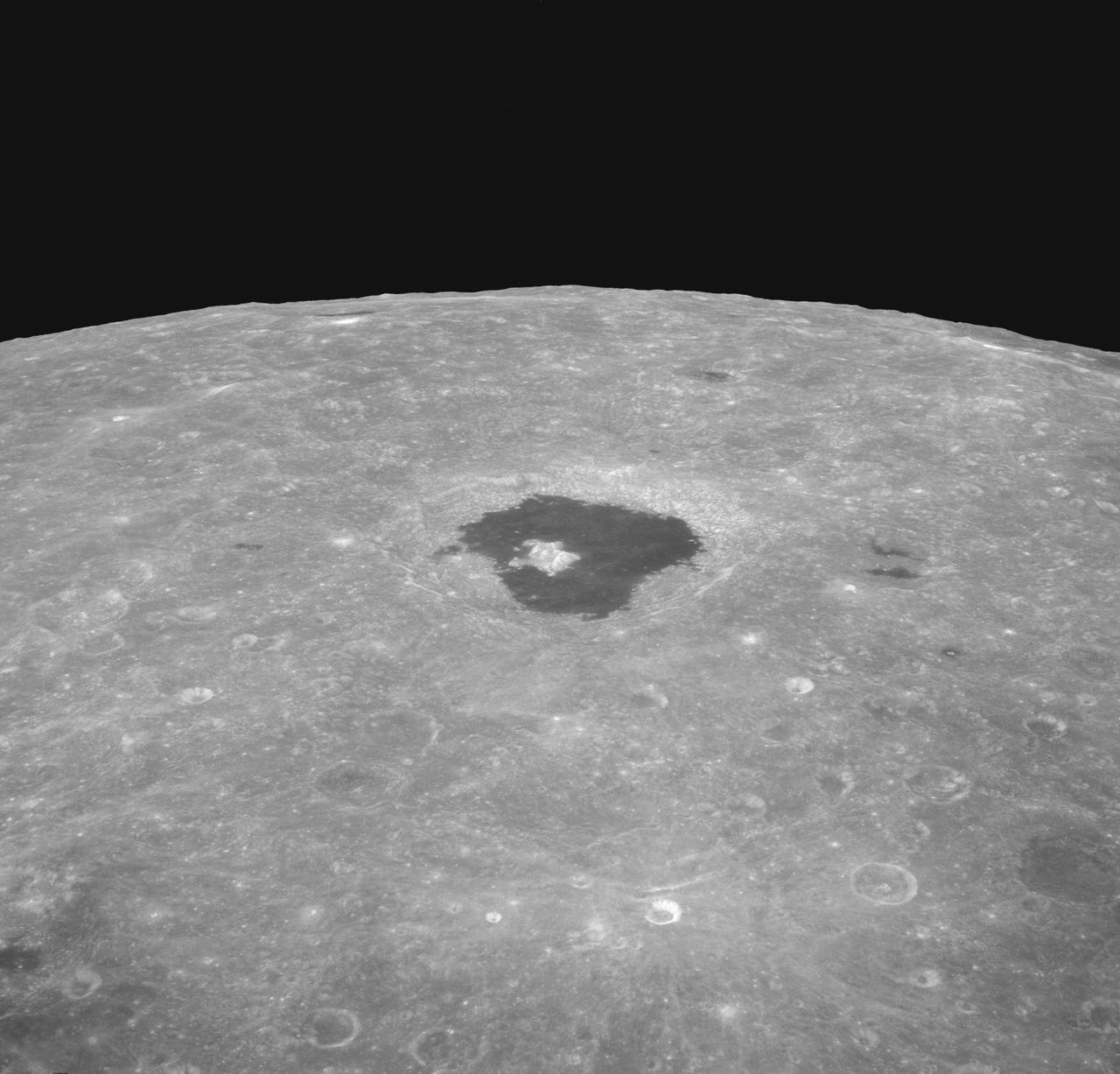

An oblique view from the Apollo 8 spacecraft looking eastward across the lunar surface. The crater Tsiolkovsky in the centre of the picture is 150 km (93 miles) wide and is located at 129 degrees east longitude, 21 degrees south latitude.

North American Rockwell artist's concept of a crucial phase of the Apollo 8 lunar orbital mission. Here, after 20 hours of lunar orbit, the astronauts have fired the SPS engine to begin the journey home.

Image courtesy of North American Rockwell and NASA

The new target. After the successful firing of the SPS engine, Apollo 8 came around the Moon for the last time on orbit 10 and began the long trip home.